Section 498A Misuse Debate Reopens — Centre Proposes Mediation Framework for Marital Disputes

- ByAdmin --

- 21 Apr 2025 --

- 0 Comments

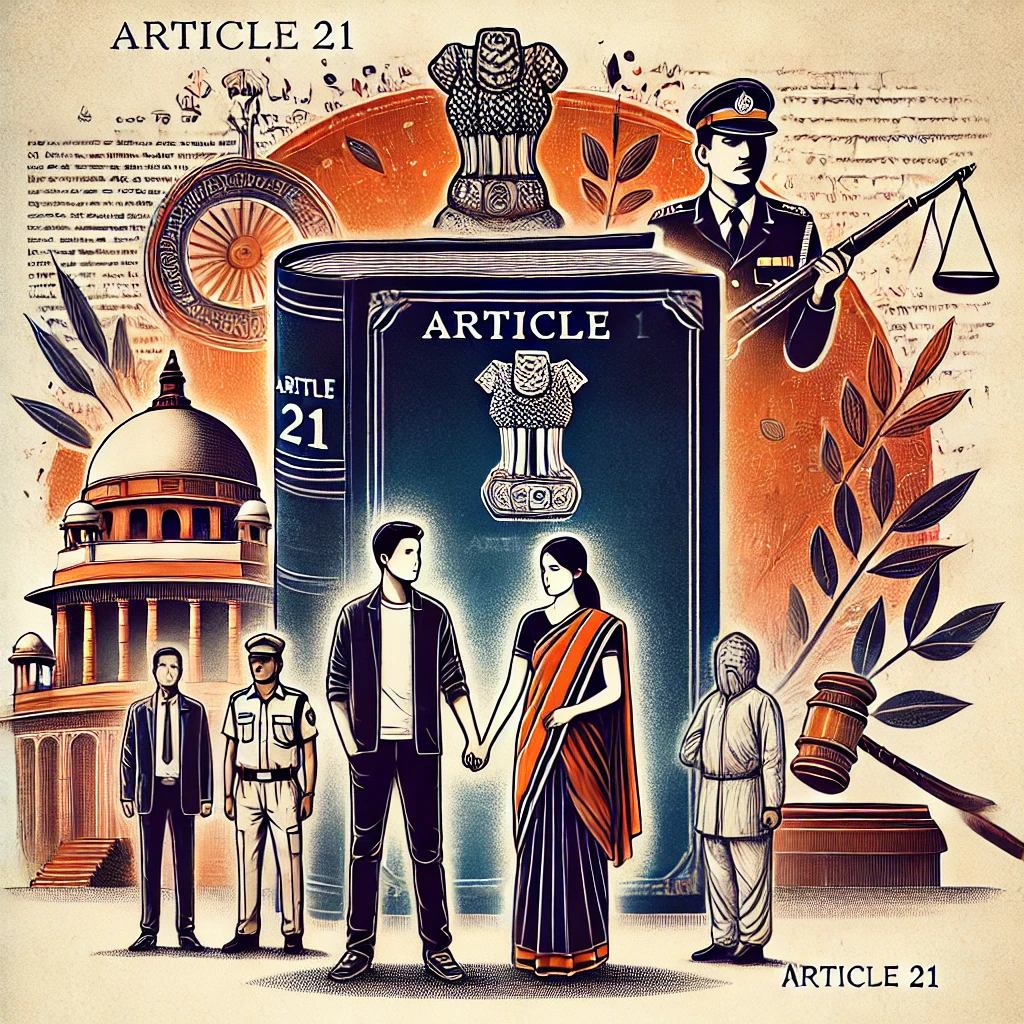

In a fresh development that reignites one of the most controversial debates in Indian matrimonial law, the Union Government has submitted a proposal before the Supreme Court suggesting a preliminary mediation mechanism in cases filed under Section 498A of the Indian Penal Code (IPC) — the provision that criminalizes cruelty against married women by their husbands or in-laws.

While the Centre maintains that this mediation framework will address growing misuse and prevent breakdown of marriages, critics warn that it may weaken vital legal protections for domestic violence survivors and delay justice in genuine cases.

Understanding Section 498A: A Double-Edged Sword?

Section 498A IPC was enacted in 1983 to combat rising incidents of dowry harassment and cruelty, defined as:

“Any willful conduct which is of such a nature as is likely to drive the woman to commit suicide or to cause grave injury...”

The law is non-bailable, non-compoundable, and allows immediate police intervention and arrest — designed to provide swift relief to aggrieved women in abusive marriages.

However, over the years, concerns emerged regarding its alleged misuse:

- False complaints to settle personal scores or gain leverage in divorce proceedings

- Automatic arrests without verification, leading to harassment of innocent family members

- Delayed investigations, as the system got flooded with matrimonial FIRs

- Before FIRs are registered under 498A, police should refer the couple to a family welfare or mediation cell (within 15 days).

- FIRs will be filed only if reconciliation fails or there is a threat to life and safety.

- These panels will include trained counselors, female officers, and legal aid volunteers to ensure a sensitive, non-coercive environment.

- In cases involving suicide, grievous hurt, sexual abuse, or imminent danger, immediate FIR and police action will continue as per law.

- The Centre has proposed a yearly audit of 498A cases, segregating resolved, withdrawn, or misused cases for policy review.

What the Centre Has Proposed

The Centre, responding to a PIL and several prior judicial observations, proposed the following key elements in its affidavit:

- Mandatory Mediation at Pre-FIR Stage

- Creation of Women-Centric Mediation Panels

- Exemptions for Severe Cases

- Periodic Review and Data Collection

What Prompted the Proposal?

The debate was reignited after several High Courts and National Crime Records Bureau (NCRB) data highlighted:

- Low conviction rates (around 15%) in 498A cases

- Frequent quashing of FIRs upon mutual divorce settlements

- Increasing pressure on courts due to litigation in family-related offences

- Concerns over young or elderly in-laws being dragged into protracted criminal cases

In Rajesh Sharma v. State of UP (2017), the Supreme Court had observed misuse and issued safeguards including no automatic arrest, but a larger bench diluted those directions in 2018 to protect genuine complainants.

The Centre now aims to strike a balance between redressal and reconciliation.

Supporters Say: It Will Reduce Weaponization of Law

Those supporting the proposal — including some judicial officers, retired judges, and family lawyers — argue that:

- Not all marital disputes require criminal intervention; mediation offers a chance at resolution.

- Families can avoid long trials and social stigma if reconciliation works.

- It will reduce court burden and allow focus on serious cases of cruelty or violence.

Critics Say: Mediation May Lead to Silencing of Victims

However, women’s rights organizations, legal scholars, and activists are raising red flags:

- Mediation may pressure women into returning to abusive homes, especially in conservative or rural settings.

- Many women lack legal knowledge, confidence, or support and may feel forced to compromise.

- The power imbalance in abusive relationships makes fair negotiation nearly impossible.

- Delaying FIR may risk further abuse or even death in extreme cases.

Advocate Karuna Nundy, a constitutional expert, noted:

“Dowry harassment is real. Mediation must be an option, not an obstacle. Any framework must be survivor-centric, not merely statistical.”

Legal Standing: Can FIR Be Deferred for Mediation?

Under CrPC Section 154, police are duty-bound to register an FIR immediately upon receiving information about a cognizable offence. The Supreme Court, in Lalita Kumari v. Govt. of UP (2013), held that FIR registration is mandatory, and delay can only be justified in exceptional circumstances.

Therefore, critics argue that making mediation a prerequisite may violate this binding precedent and create legal grey zones.

What Comes Next?

The Supreme Court is expected to:

- Hear all stakeholders, including NCW, NALSA, and civil society organizations

- Evaluate whether mediation before FIR violates constitutional rights

- Possibly issue guidelines balancing protection and reconciliation, especially for first-time, non-violent offences

States may also be asked to pilot mediation cells with clear safeguards before national roll-out.

Between Misuse and Misery Lies Reform

Section 498A was born out of necessity—to protect women from marital cruelty and dowry violence. But its misuse, though limited in scale, has prompted genuine calls for reform.

The Centre’s proposal is a chance to refine the law, not weaken it. Any mediation framework must empower women, not police discretion. Because between the pain of injustice and the fear of misuse, justice must never lose its moral compass.

0 comments